Part 3:Project Covid-19 Report

Australia

A brief intro to the Australian Constitution

Australia is a parliamentary democracy. The Australian Constitution of 1901 established a federal system of government in Australia. Under this system, powers are distributed between a national government (the Commonwealth) and the six states. The Constitution defines the boundaries of law-making powers between the Commonwealth and the States/Territories.

As well as the six states (New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia), there are three self-governing territories – Australian Capital Territory, Northern Territory, and Norfolk Island.

The spread of the virus

The first COVID 19 case was confirmed by Victoria’s Health Authorities on 25th January 2020. The patient, a man from Wuhan, flew to Melbourne from Guangdong on 19 January. Following this first case, the actions taken by the government have been analysed below.

Reflecting on what was successful and what could have done better

These lessons should inform the next stage of Australia’s response as we transition to a new normal.

Four successes

Australia has avoided the worst of the pandemic. Comparable countries, such as the U.K. and U.S., are mourning many thousands of lives lost and are still struggling to bring the pandemic under control. The reasons for Australia’s success story are complex but four factors have been important.

Success 1: Cooperative governance informed by experts

The formation of a ‘National Cabinet’, comprising the Prime Minister and the leaders of each state and territory government, was a key part of Australia’s successful policy response to COVID-19.

The states and territories have primary responsibility for public hospitals, public health, and emergency management, including the imposition of lockdowns and spatial distancing restrictions. The Commonwealth has primary responsibility for income and business support programs. Coordination of these responsibilities was critical.

The National Cabinet was created quite late – in mid-March when cases were beginning to increase exponentially – it has proven to be an effective mechanism to resolve most differences and coordinate action as much more dramatic and far-reaching measures were put in place.

Within a week since the formation of the National Cabinet, Australia began to implement restrictions on social gatherings progressively. On 22 March, in advance of a National Cabinet meeting that evening, Victoria, NSW, and the ACT announced they were proceeding in the next 48 hours to implement a shutdown of all non-essential activity. This helped push all other governments into widespread business shutdowns announced by the Prime Minister that night, to take effect the following day.

National cooperation was enhanced further by the inter-jurisdictional Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC). From the start of the crisis, this forum helped underpin Australia’s decisions with public health expertise. The AHPPC’s recommendations informed government decisions, particularly the expansion of spatial distancing measures. It is now commonplace to have the Prime Minister give a national press briefing alongside the Chief Medical Officer, who chairs the AHPPC.

The Commonwealth Government was criticised, however, for announcing it was suspending Parliament. While the Commonwealth was making significant national decisions, including record spending commitments, the suspension meant the Government had minimal formal oversight. To at least partially overcome this deficiency, on 8 April the Senate set up a select committee to provide some checks and balances on the Government’s response.

Success 2: Closure of international borders and mandatory quarantine

Closure of international borders and mandatory quarantine Australia’s decision to close its borders to all foreigners on 20 March to ‘align international travel restrictions to the risks’ was a turning point in Australia’s response. The overwhelming number of new cases (about 90 per cent) during the peak of the crisis came from or were linked directly to someone who had been overseas. This marked the start of Australia’s ‘escalated national action’ phase. Within two weeks of Australia’s borders being closed to foreigners, Australia’s daily case numbers began to fall.

And once this measure was coupled with mandatory quarantine at designated facilities for all Australian international arrivals a week later, Australia had much more control over the spread of the virus.

Success 3: Australia’s rapid adoption of spatial distancing measures reduced the risk of community transmission.

Italy was particularly hit the hardest, overtaking China’s death toll by mid-March. In the most affected regions of Italy, the health system was close to collapse. Once Australians could see the risk of the virus overwhelming the nation’s health system, highlighted by Italy’s struggling health system at the brink of collapse, people quickly complied with shutdown laws. Australians had already begun reducing their activity before the restrictions were imposed.

Australians’ successful compliance is demonstrated by the low number of community transmissions, despite having less-strict lockdown laws than some other nations such as France and New Zealand.

Success 4: Expansion of telehealth

One of the Commonwealth’s early healthcare interventions was to expand Australians’ access to telehealth radically. Telehealth enables patients to consult health professionals via video conference or telephone, rather than face-to-face.

This means healthcare workers and patients can remain home rather than put themselves into a higher-risk setting such as a healthcare clinic or a doctor’s waiting room.

The Commonwealth announced the first of these measures in its $2.4 billion health package on 11 March and quickly phased in broad-scale telehealth services for all Australians. Within six weeks, over 250 new ‘temporary’ items had been added to the Medicare Benefits Schedule, which extends to seeking advice from allied health workers and specialists. These changes were complemented with changes to medication services, enabling electronic delivery of prescriptions to the pharmacy, with options for patients to have medications delivered to their homes.

Australians have enthusiastically taken up telehealth services, with more than 4.3 million medical and health services delivered to three million patients in the first month. A RACGP survey of over 1,000 GPs found that 99 per cent of GP practices were now offering telehealth services, with 97 per cent also continuing to offer face-to-face consultations.

Four failures

Unfortunately, Australia has also had failings. The most obvious is the handling of the Ruby Princess cruise ship, but Australia might have been in a better position today if it had acted against the virus more quickly and if its leaders had been more clear about where they were heading.

Australia eventually ‘went hard’, but it was too slow to get started. The Commonwealth Government spent too long in the early days flailing in uncertainty about the scale of the crisis. As a result of this hesitancy, the Government was too slow to shut international borders and to prepare the healthcare system for the possibility of a huge influx of COVID-19 patients.

Failure 1: The Ruby Princess

About 2,700 Ruby Princess passengers were allowed to disembark freely in Sydney on 19 March, despite some showing COVID-19 symptoms. The ship was ultimately linked to at least 900 infections (about 3% of the total cases of the country) and 28 deaths (about 3% of the total deaths in Australia). Before Australia’s second wave of the virus – which emerged in Melbourne in June – the cruise ship had been the source of Australia’s biggest coronavirus cluster.

On 15 April, NSW launched a Special Commission of Inquiry to investigate what went wrong and on 5 May a Commonwealth Senate Select Committee on COVID-19 inquired into the case. NSW police will also spend the next six months investigating what was known about the potential coronavirus cases before the Ruby Princess was allowed to dock.

Failure 2: Too slow to close the borders

Australia spent too long in the uncertainty phase during the early stages of the crisis. While Australia was comparatively quick to ban foreign nationals coming from China, it was slow to introduce any further travel restrictions. As the virus spread worldwide, Australia continued to have thousands of international arrivals each day. It took more than six weeks after Australia’s first confirmed case for the Government to introduce universal travel restrictions – first requiring self-isolation for all international arrivals (on 15 March), followed by the borders closing to foreign arrivals (on 20 March). Before this, travel restrictions were targeted at specific countries (e.g. South Korea, Iran and Italy) inconsistently, despite some other countries such as the U.S. posing a similar or greater risk.

Failure 3: Too slow to prepare the health system

Australia was too slow to prepare the health system in advance of the pandemic rapidly spreading in Australia. The initial focus on containment, followed by caution and uncertainty, distracted governments from preparing their health systems early. This meant that when cases began to rise exponentially, Australia was not fully prepared for a pandemic-scale response. This was particularly evident in Australia’s testing regime. At first, some people with symptoms went to community GP clinics or hospitals, putting others at risk. On 11 March the Commonwealth Government announced 100 testing clinics would be established, but this was only completed two months later, once the peak of the crisis had passed.

As cases began to increase in mid-March, Australia very quickly hit supply shortages for testing. The testing regime remained narrow for too long before new testing kits could be acquired. This meant that many people with symptoms could not be tested, increasing the chances of community transmission. Broader community testing, led by state governments, did not begin until April.

Australia also struggled to get enough personal protective equipment (PPE) quickly enough to meet demand. Australia’s initial national stockpile of 12 million P2/N85 masks and 9 million surgical masks was not enough. Supplies of gowns, visors, and goggles had also not been set aside in Australia’s national stockpile in the event of a crisis. General practitioners complained of inadequate supplies hampering their work. Eventually, on 26 March, elective surgery was severely curtailed so that PPE could be diverted to frontline health workers dealing with the pandemic.

As shortages loomed, Australian health departments joined global bidding competitions for fast-track supplies from overseas manufacturers. Some state governments turned to local manufacturers to boost supplies.

Failure 4: Shifting strategies and mixed messages

The lack of a clear overarching strategy to respond to the crisis has resulted in a reactive policy approach. This has led to mixed and confusing messages. At first, there was confusion about the shutdown measures: which businesses or events should close (for example, the Grand Prix). There have been inconsistencies between the Commonwealth’s position and the states’. For example, most states closed or partially closed their public schools around Easter and began re-opening them when cases went down over a month later. Despite concerns raised by some state governments, the Commonwealth asserted children were not at risk, with the Prime Minister repeatedly encouraging parents to send their children to school. Childcare centres also remained open.

The mixed messages have been pronounced particularly on Australia’s strategy to manage the virus. Initially, the Commonwealth Government talked about ‘slowing the spread’, but some states argued for a ‘stop the spread’ strategy. This tension increased confusion about how far Australia’s lockdown restrictions should go. Debate raged between people who argued that ‘herd immunity’ was Australia’s only option, and people who pushed for the ‘elimination’ of COVID-19 in Australia.

When clarity was sought from the Commonwealth, the messaging remained unclear. Even the statement from the Prime Minister on 16 April, designed to clarify the Commonwealth’s position on its longer-term strategy, confused two different strategies as one, by saying Australia was continuing to ‘progress a successful suppression/elimination strategy for the virus’. But even as the debate raged on, the case count forged its own story, showing that elimination may be possible as more and more states began to record multiple days and weeks with no new cases.

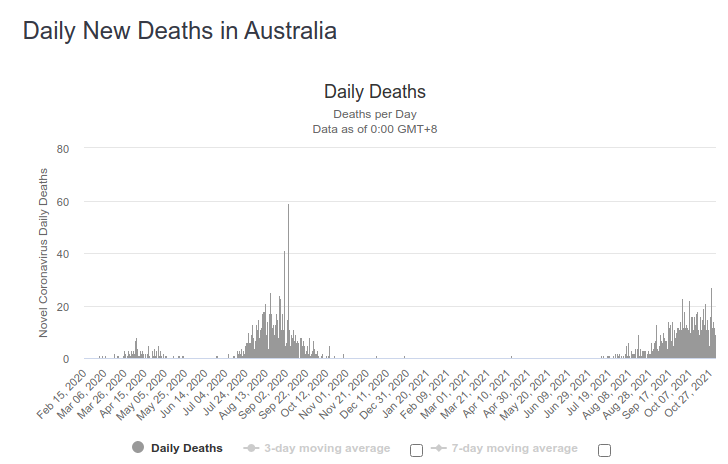

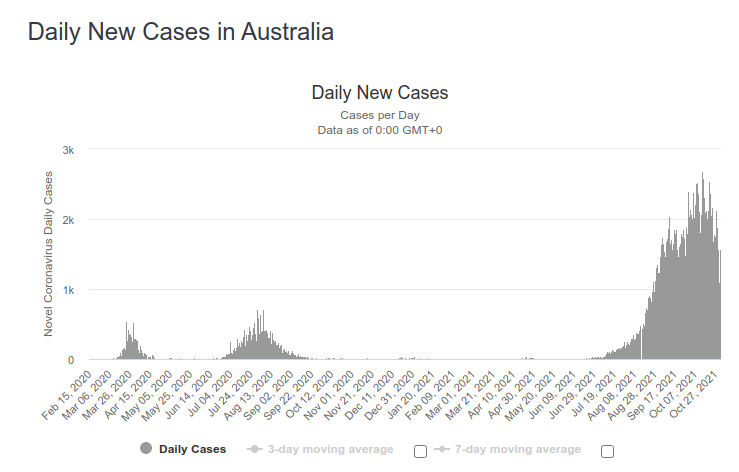

The below graphs show the variation of daily new cases and the daily deaths respectively;

COVID-19 testing data

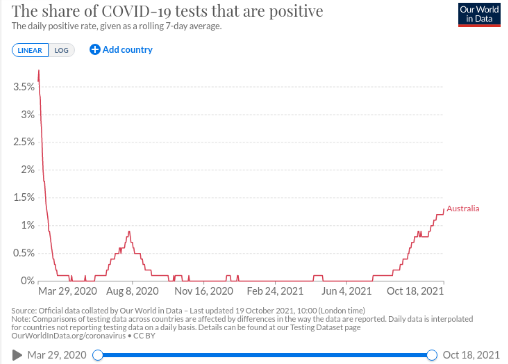

1. Positive rate

The positive rate is calculated by dividing the number of cases by the number of tests conducted.

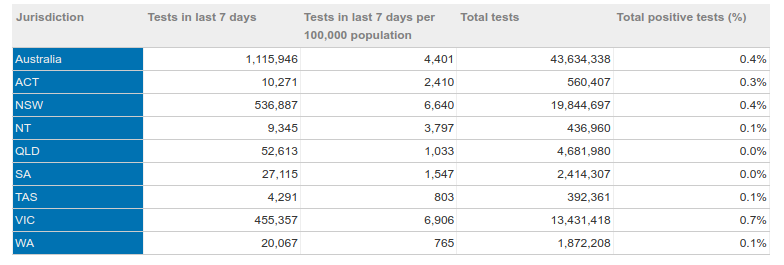

The below table shows the positive rate for The COVID 19 tests conducted in total last 7 days and their results

Source: Department of Health, States & Territories Report 2/11/2021

The graph below shows the variation of the positive rate with time;

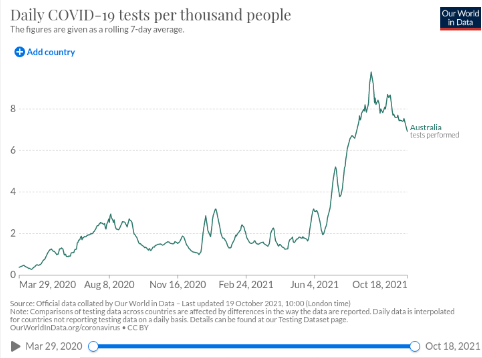

2. Test per thousand people

The graph below shows the variation of daily tests;

This graph shows the number of COVID 19 cases currently admitted to the hospital, including.

Total COVID-19 cases in Australia by the source of infection

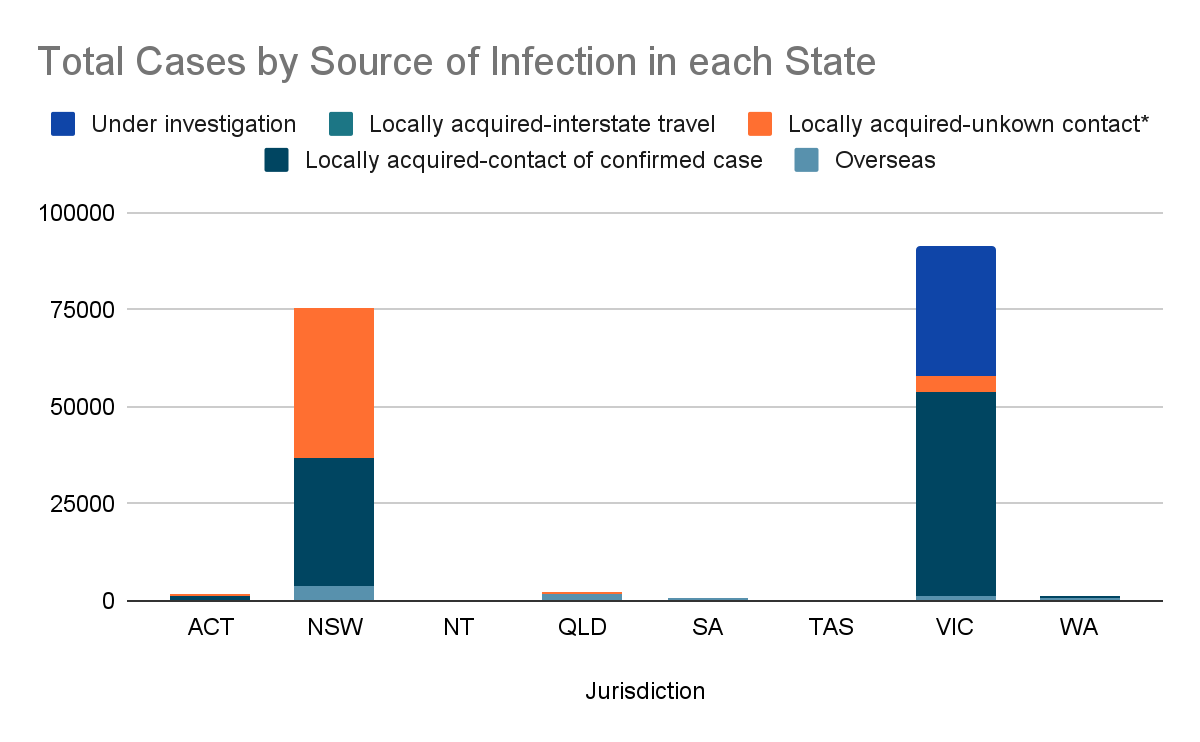

This chart shows the total number of COVID 19 cases in each state and territory since the first case was reported, by the source of infection;

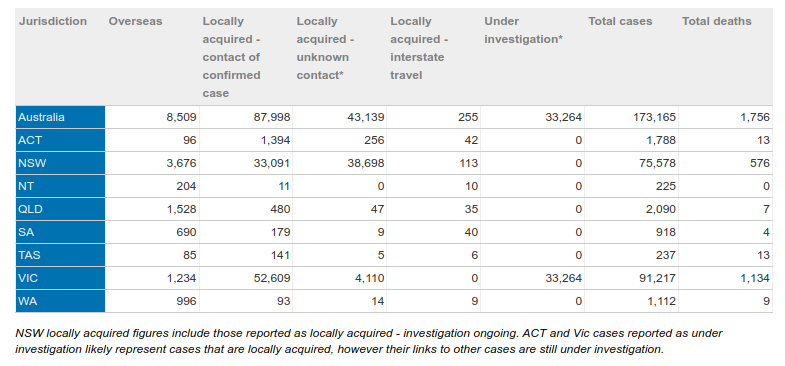

The table corresponding to this graph is given below;

Source: Department of Health, States & Territories Report 2/11/2021

Comparing genders and ages

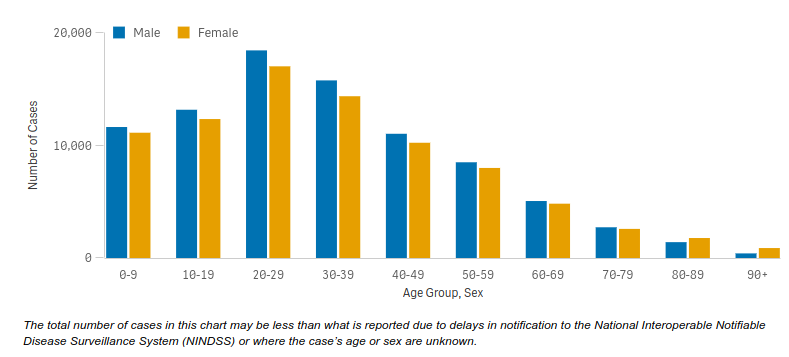

This graph shows the number of COVID 19 cases in Australia for males and females by age group since the first reported case;

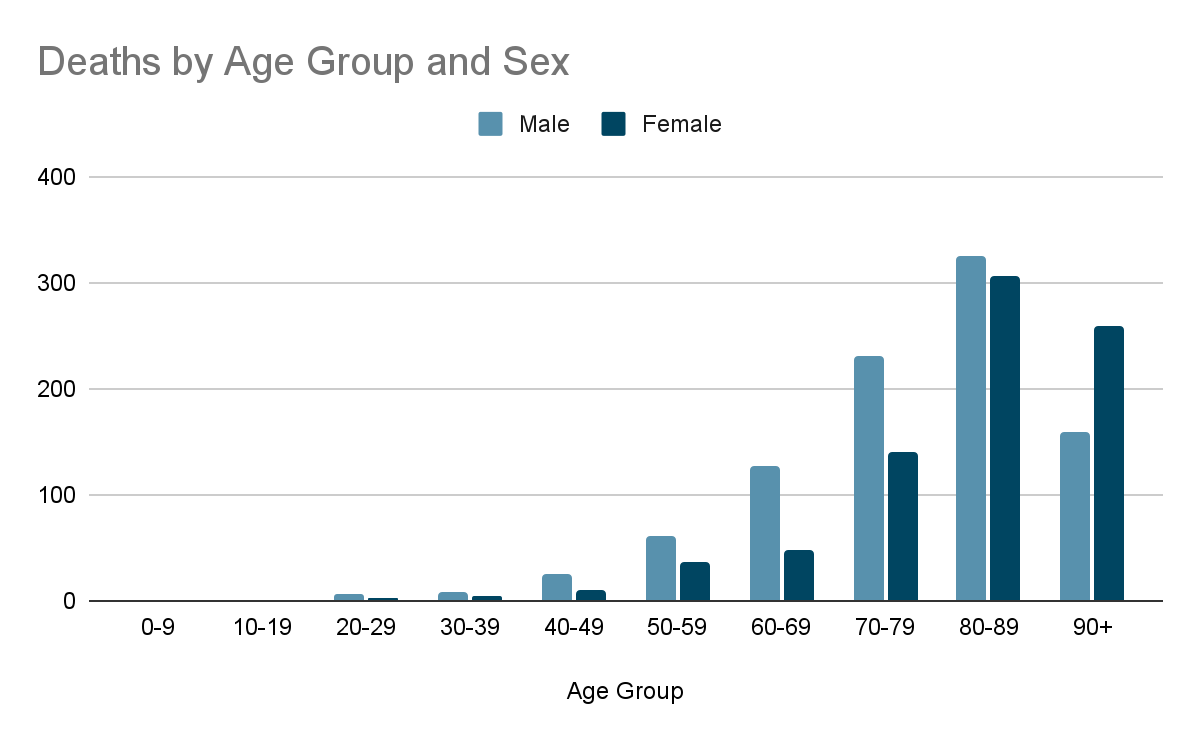

This graph shows the number of COVID 19 associated deaths in Australia for males and females by age group since the first reported case;

The total number of deaths in this chart may be less than what is reported due to delays in notification to the National Interoperable Notifiable Disease Surveillance System or where the case’s age or sex is unknown.

Vaccination

Australia began vaccination in late February.

The vaccines approved for use in Australia are;

- Moderna

- Pfizer/BioNTech

- Janssen (Johnson & Johnson)

- Oxford/AstraZeneca

The following chart gives an idea of the current progress of vaccination for the total population of Australia. (as of 2/11/2021)

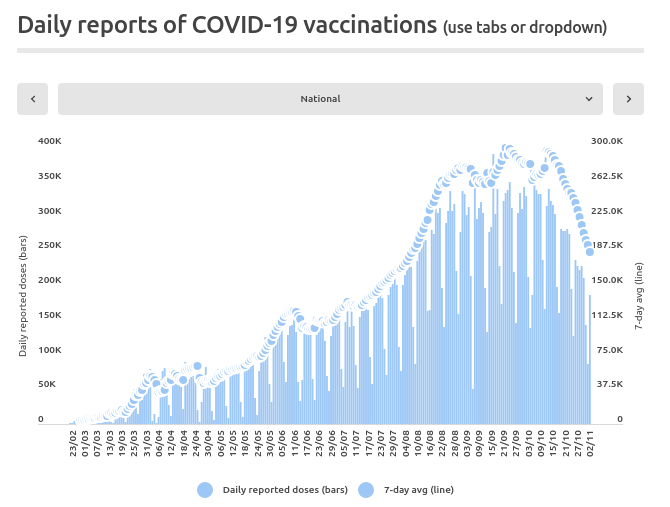

The daily reports of vaccinations are shown below (as of 2/11/2021)

Resources:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-53802816#:~:text=The%20ship

https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov- health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-current-situation-and-case-numbers#daily -reported-cases https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/australia/ https://libguides.anu.edu.au/c.php?g=634887&p=4547083#:~:text=Australi a%20is%20a%20parliamentary%20democracy,Commonwealth)%20and% 20the%20six%20States

deborahalupton.medium.com grattan.edu.au

https://www.covid19data.com.au/

New Zealand

The Alert System

|

Level |

Risk assessments |

Range of measures |

|---|---|---|

|

Level 4- Lockdown Likely that the disease is not contained |

● Sustained and intensive transmission ● Widespread outbreaks |

|

|

Level 3- Restrict A heightened risk that the disease is not contained |

● Community transmissions occurring OR ● Multiple clusters breaking out |

|

|

Level 2- Reduce Low risk of community transmission |

OR

|

using public transport, aeroplanes (including in departure points such as train/bus stations and airports) and in a taxi or ride-share vehicle visiting a healthcare or aged care facility (other than for a patient) inside retail businesses, such as supermarkets, pharmacies, shopping malls, indoor marketplaces, takeaway food stores and public venues — such as museums and libraries visiting the public areas within courts and tribunals, local and central government agencies, and social service providers with customer service counters providing services while on-site in a home or places of residence (except for providing childcare).

as a driver of a taxi or ride-share vehicle at close contact businesses, for example; barbers, beauticians and hairdressers in a public-facing role at a hospitality venue, for example; a cafe, restaurant, bar or nightclub at retail businesses, such as supermarkets, shopping malls, indoor marketplaces, takeaway food stores in the public areas of courts and tribunals, local and central government agencies, and social service providers with customer service counters at indoor public facilities, for example; libraries and museums (but not swimming pools). |

|

Level 1- Prepare Disease is contained |

● COVID-19 is uncontrolled overseas. OR ● Sporadic imported cases OR ● Isolated local transmission |

Note that exclusions apply to people with disabilities or mental health conditions. |

- Currently, Auckland and some parts of Waikato are at level 3 while the rest of New Zealand is under level 2.

- Restrictions are cumulative, for example at Alert Level 4, all restrictions from Alert Levels 1, 2 and 3 apply.

The spread of the virus

New Zealand reported its first case of covid-19 on 28 February, a person in their 60s who has travelled to Auckland from Iran. The government placed restrictions on people travelling to New Zealand from Iran. On 4 March, an Auckland woman in her 30s, who visited northern Italy, was confirmed as the second case of Covid-19 in New Zealand. The next day, the third case of covid-19 is confirmed in Auckland in a man in his 40s whose family recently travelled from Iran. This is the first known person-to-person transmission in New Zealand.

On 6 March a fourth case of the virus was confirmed in New Zealand in an Auckland man in his 30s. He is the partner of the second case, announced on 4 March. On 7 March the fifth case of covid-19 is confirmed in New Zealand – an Auckland woman in her 40s who is the partner of the third case. On 15 March two more people tested positive for the virus in New Zealand – a man in his 60s visiting Wellington from Australia; and a woman in her 30s from Denmark, who is in Queenstown. This brings the number of confirmed cases in New Zealand to eight. There are an additional two probable cases. Thus the virus started to spread in areas other than Auckland.

A probable case is an individual who has not had a confirmatory test performed but has a positive antigen test and/or clinical criteria of infection and is at high risk for COVID-19 infection.

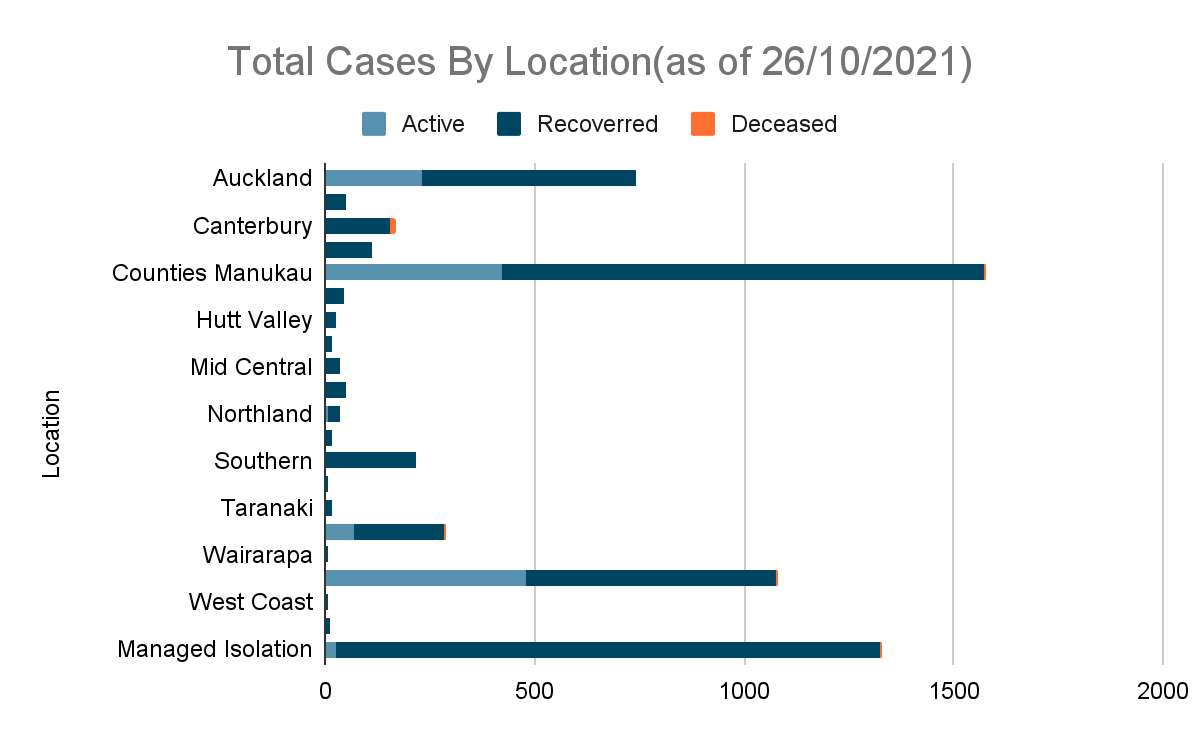

|

Total cases by location (as of 26/10/2021) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Location |

Active |

Recovered |

Deceased |

Total |

Change in last 24 hours |

|

Auckland |

232 |

509 |

1 |

742 |

14 |

|

Bay of Plenty |

0 |

48 |

0 |

48 |

0 |

|

Canterbury |

0 |

156 |

12 |

168 |

0 |

|

Capital and Coast |

0 |

111 |

2 |

113 |

0 |

|

Counties Manukau |

424 |

1151 |

2 |

1577 |

33 |

|

Hawk’s Bay |

0 |

44 |

0 |

44 |

0 |

|

Hutt Valley |

0 |

24 |

0 |

24 |

0 |

|

Lakes |

0 |

16 |

0 |

16 |

0 |

|

Mid Central |

0 |

33 |

0 |

33 |

0 |

|

Nelson Marlborough |

1 |

49 |

0 |

50 |

0 |

|

Northland |

7 |

28 |

0 |

35 |

0 |

|

South Canterbury |

0 |

17 |

0 |

17 |

0 |

|

Southern |

0 |

215 |

2 |

217 |

0 |

|

Tairāwhiti |

0 |

4 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Taranaki |

0 |

16 |

0 |

16 |

0 |

|

Waikato |

66 |

218 |

2 |

286 |

4 |

|

Wairarapa |

0 |

8 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

|

Waitematā |

479 |

599 |

5 |

1083 |

27 |

|

West Coast |

0 |

4 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

|

Whanganui |

0 |

9 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

|

Managed Isolation & Quarantine |

23 |

1303 |

1 |

1327 |

-5 |

|

Total |

1232 |

4562 |

28 |

5822 |

73 |

Imported cases are foreign individuals who tested positive to corona on arrival to a country.

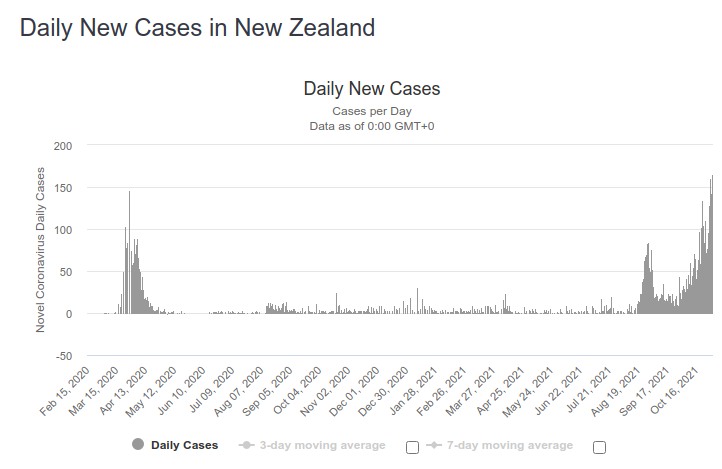

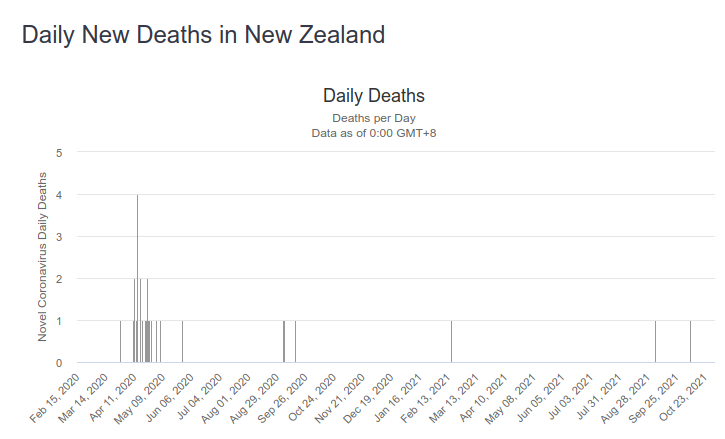

The below graphs shows the variation of daily cases and daily covid deaths respectively;

COVID-19 testing data

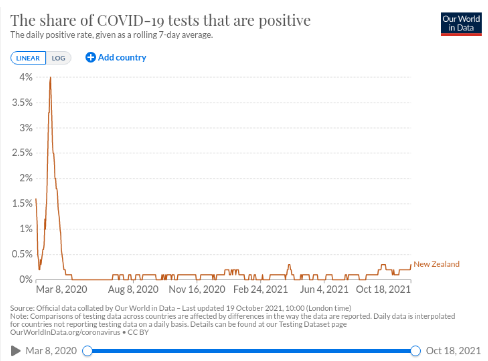

The graph below shows the variation of the positive rate from March 2020 to October 2021;

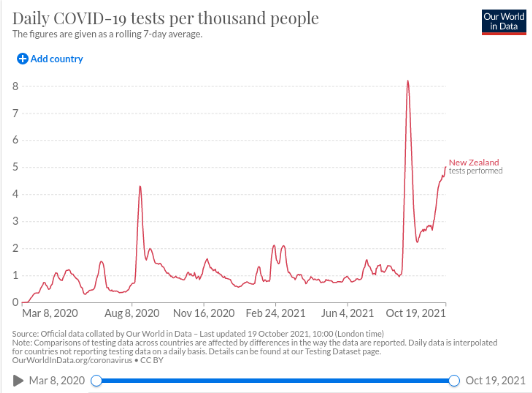

2. Tests per thousand people – The graph below shows the variation of the number of tests conducted over from March 2020 to October 2021;

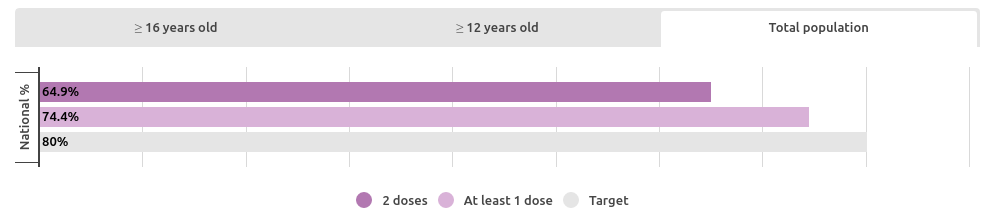

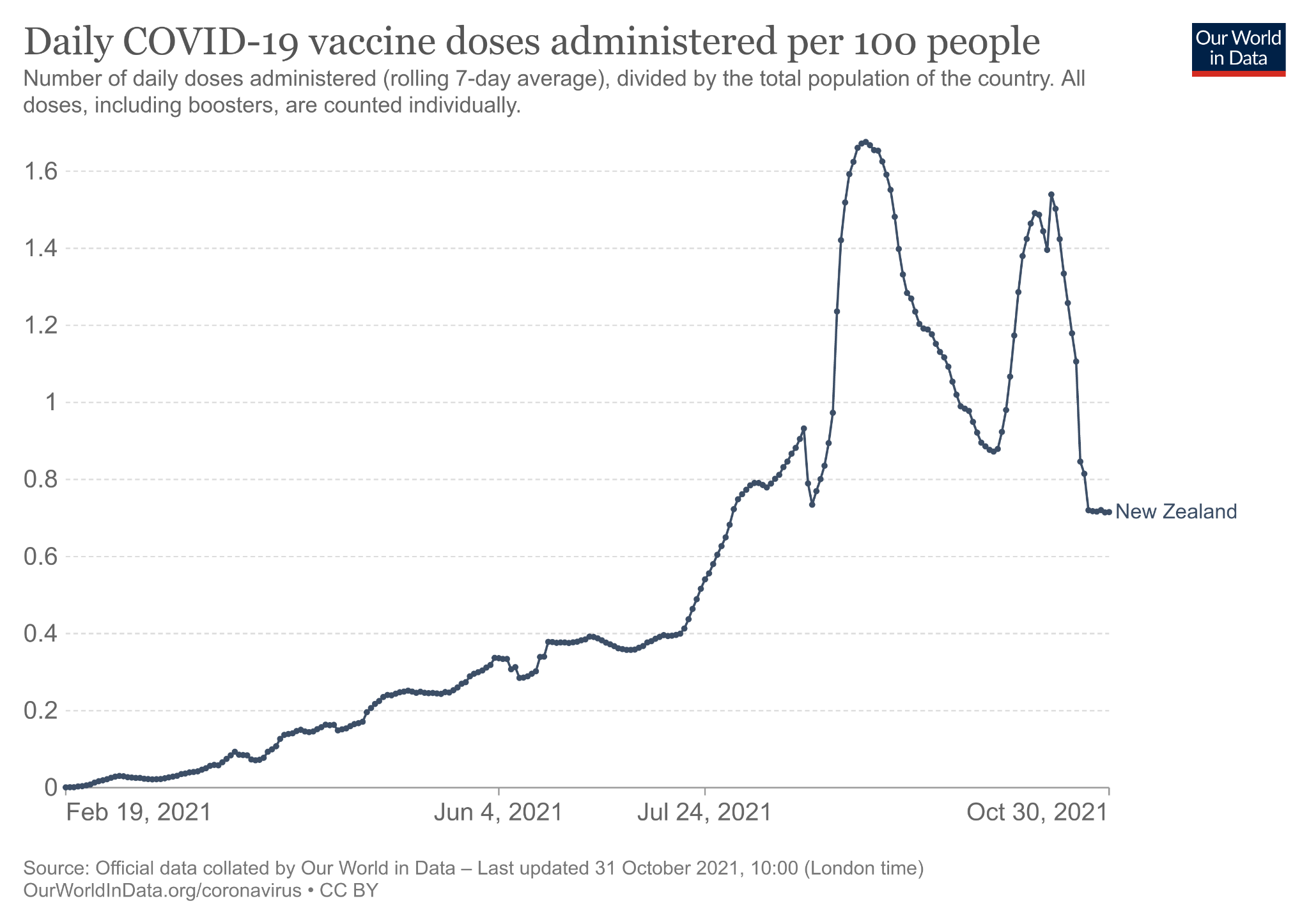

Vaccination

New Zealand started vaccination in late February. Furthermore, they plan to re-open the country to the world after vaccinating 90% of their population.

The vaccines recommended for use by the government are;

BioNTech, Pfizer vaccine

Johnson & Johnson vaccine

Oxford, AstraZeneca vaccine

Currently, 65% of the population are fully vaccinated against COVID 19, while 12% are only partially vaccinated.

The following table shows cumulative vaccinations by ethnicity as of 31st October;

|

Ethnicity |

First dose administered |

First doses per 1,000 people |

Second dose administered |

Second doses per 1,000 people |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Māori |

410,683 |

719 |

300,709 |

527 |

|

Pacific Peoples |

244,009 |

851 |

197,188 |

688 |

|

Asian |

607,681 |

>950 |

543,063 |

907 |

|

European/Other |

2,412,941 |

884 |

2,089,841 |

765 |

|

Unknown |

34,001 |

– |

28,500 |

– |

|

Total |

3,709,315 |

881 |

3,159,301 |

751 |

*doses per 1,000 are based on eligible (12+) of the relevant ethnic group.

Resources

https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-nov el-coronavirus/covid-19-data-and-statistics/covid-19-current-cases https://covid19.govt.nz/alert-levels-and-updates/

https://shorthand.radionz.co.nz/coronavirus-timeline/ https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/new-zealand/

https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations?country=NZL

China

On Dec. 31, 2019, Chinese authorities alerted the World Health Organization of pneumonia cases in Wuhan City, Hubei province, China, with an unknown cause. What started as a mystery disease was first referred to as 2019-nCoV and then named COVID-19.

It also shares a lot of similarities with two other coronaviruses, the MERS-CoV (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) and SARS-CoV (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome). The outbreak of the COVID-19 started with the report of a first suspected case on December 8, 2019, in Wuhan. The first two months of the epidemic covered three significant holidays, including the New Year of 2020, the Chinese New Year’s Day with vacations from January 24 to February 2, 2020, and the Lantern Festival on February 8, 2020.

China officially declared the epidemic as an outbreak on January 20 when obvious human-to-human transmissions were ascertained with reagent probes and primers distributed to local agencies on that day. Immediately following the declaration, massive actions were taken the next day to curb the epidemic at Wuhan, and soon spread to the whole country from central to local government, including all sectors from business to factories and schools. On February 23, 2020, Wuhan City and other cities along with the main traffic lines around Wuhan were locked down. Rigorous efforts were devoted to;

1) identify the infected and bring them to treatment in hospitals for infectious diseases

2) locate and quarantine all those who had contact with the infected

3) sterilise environmental pathogens

4) promote mask use

5) release to the public the number of infected, suspected, under treatment and deaths daily.

However, the sudden escalation of the control and the spread of the number of infected and deaths ignited fear and panic among people in Wuhan. The negative emotional responses soon spread from Wuhan to other parts of China, and further to the world via almost all communication channels, particularly social media. The highly emotional reactions of the public were fueled by;

(1) sudden increases in the number of detected new cases after the massive intervention measures to identify the infected

(2) massive growing needs for masks

(3) a large number of suspected patients waiting to confirm their diagnosis

(4) a large number of diagnosed COVID-19 patients for treatment

(5) a growing number of deaths, despite national efforts to improve therapy, including the decision to build two large hospitals within days.

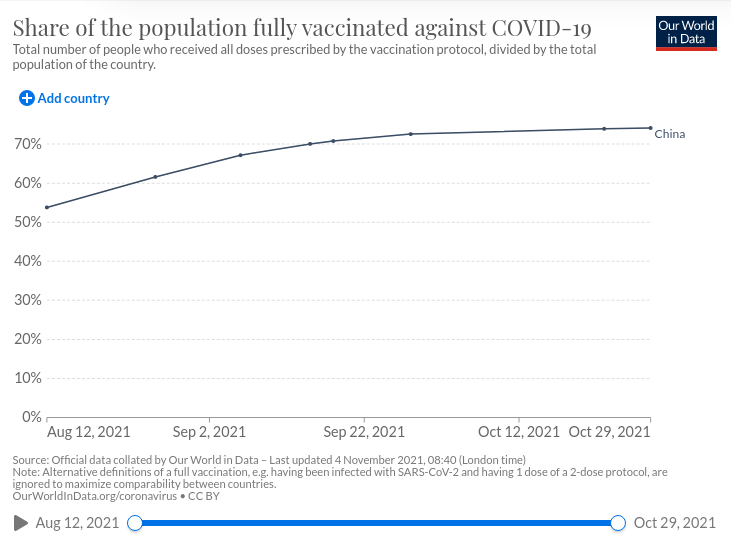

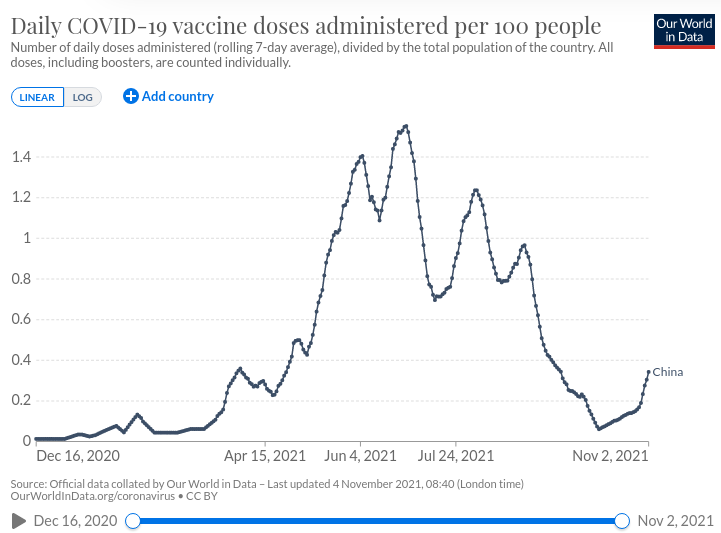

China began rolling out vaccine boosters across the country in late October. Details of the schemes vary from one city to another, but many places recommend those aged 18 to 59 – who were fully vaccinated more than six months ago – to get a third dose with the same vaccine used for the second dose. If that vaccine is in short supply, the vaccine used in the first dose can be used instead, but the third dose must use the same technology as the first two vaccines. In some places, the elderly and high-risk groups are given priority. Shao Yiming, one of China’s top epidemiologists, said in an interview that receiving a different coronavirus vaccine as a booster could spark a stronger immune response, but that the government would need more scientific data before they could approve such an approach. The mRNA vaccine developed by Germany’s BioNTech and Fosun Pharma hasn’t been approved and was not mentioned in local governments’ booster vaccine schemes.

Vaccinations

- CanSino vaccine

- CoronaVac vaccine

- RBD-Dimer vaccine

- Sinopharm BBIBP vaccine

- Sinopharm Wuhan vaccine

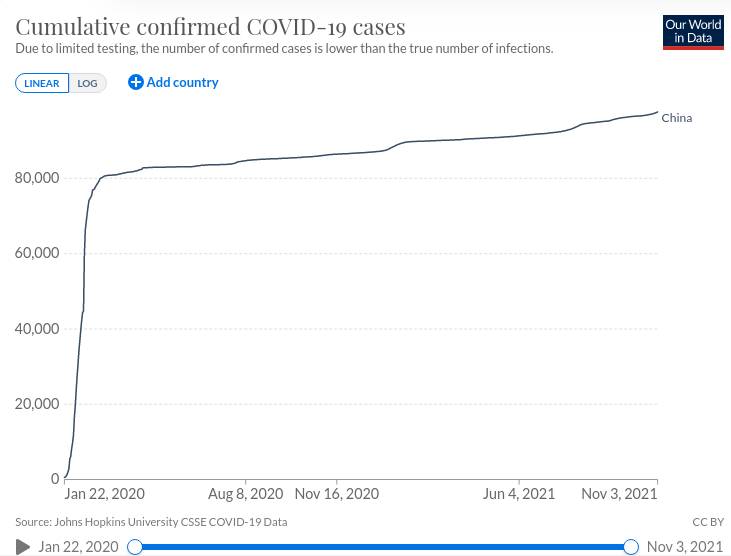

Total covid cases 97,527 total covid deaths 4,636 recovered 91,811

Resources

https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/china/

https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/china

https://ghrp.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41256-020-00137-4

We hope you gained insight into COVID 19 from our project and gained valuable knowledge. Let us know your opinions in the comment section.